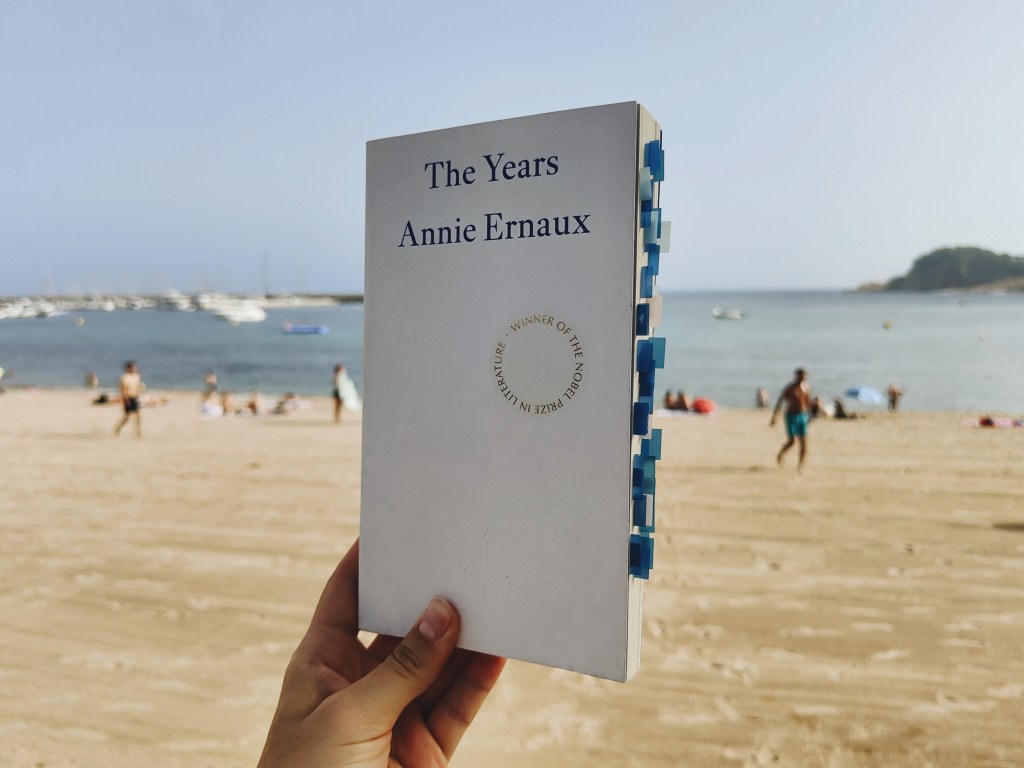

This book will probably be one of those that I will pick up again and again throughout the years. The sheer amount of passages that I highlighted speaks for itself (as you can see on the photo in the bottom of the post). From stylistically beautiful phrases, to clever observations or reflections on life as a woman that inspire to search for similar ones in one’s own life. I think that depending on the age that you read this book at, different parts might speak to you more. I’d compare it to the phenomenon of the “Sex and the City” TV series, which you can watch an endless amount of times. Depending on the issues that you’re going through in your life at that specific moment, you’d be noticing bits and pieces that you haven’t paid attention to before, which I can see happening with this book as well.

My only issue with “The Years” was that it was too France-centric and it was impossible for me to fully get the meaning of all things referenced. Having started reading it in French, I quickly switched over to the English translation because I felt like I couldn’t follow the storyline properly. It’s only after diving into the translation that I realised that it was difficult to keep up with it in English as well. Cultural references like songs, singers, kids’ rhymes, TV shows, movies, actors, as well as numerous historical events, both very big and very small, were mentioned, which I have never heard of before. I can see somebody French really enjoying this book more and it’s the only reason why I personally decided to reduce one star from the final rating. Here an example of what many passages will read like:

the dashing figure of the actor Philippe Lemaire, married to Juliette Gréco […]

of Elizabeth Drummond, murdered with her parents on a road in Lurs in 1952

p. 13

It became shameful to hope for revolution, and we didn’t dare admit that we were saddened by Ulrike Meinhof’s suicide in prison. Through some obscure reasoning, Althusser’s crime of choking his wife to death in bed one Sunday morning was blamed as much on the Marxism he embodied as on any kind of mental problem.

p. 122

If you were to look up the details of each of those descriptions (which I was trying to do in the beginning), you would get a really detailed understanding of the French society and their collective memory. I couldn’t stick to it throughout the whole book though, as it kept interrupting the reading flow. Nevertheless, imagining the author putting together the sheer amount and the details of these events, selecting the most significant ones for each year or each decade, was definitely impressive. The choice of the footnotes was therefore quite interesting, how some things were explained and others weren’t. In my case I would have needed about four times more footnotes than the amount that was provided. Another specificity that I noticed since I compared the French original and the English translation throughout the first 30 pages, was how I ended up highlighting different passages in each language. I found some phrases more beautiful in French, whereas others spoke to me more in English. I’d therefore surely try reading the book completely in its original version at some point.

notre mémoire est hors de nous, dans un souffle pluvieux du temps

p. 17 (French original)

Sitôt rentrés à la maison, on retrouvait sans y penser la langue originelle, qui n’obligeait pas à réfléchir aux mots, seulement aux choses à dire ou à ne pas dire, celle qui tenait au corps, liée aux paires de claques, à l’odeur d’eau de Javel des blouses, des pommes cuites tout l’hiver, aux bruits de pisse dans le seau et aux ronflements des parents.

p. 35 (French original)

The style the book was written in was definitely something that you would enjoy while reading. I even felt like reading some passages out loud because the rhythm of the words flowed so beautifully! The content was just as fascinating. Seeing the transition of society from the 1940s until 2006 through the shape of a collective memory, as well as influenced by the author’s personal stories told in the third person, was definitely something that I haven’t read in such a form before. From a society where hardly anyone traveled, hardly threw anything away, up until the current day times in the era of disposability, mobile phones, computers and all types of modern technology. It was really eye-opening, having the speed of how everything in our lives changed in a span of just about 70 years demonstrated in writing.

How to make the fresco of forty-five years coincide with the search for a self outside of History, the self of suspended moments transformed into the poems she wrote at twenty (‘Solitude’, etc.)? Her main concern is the choice between ‘I’ and ‘she’. There is something too permanent about ‘I’, something shrunken and stifling, whereas ‘she’ is too exterior and remote.

p. 167-168

Nothing was thrown away. The contents of chamber pots were used for garden fertilizer, the dung of passing horses collected for potted plants. Newspaper was used for wrapping vegetables, drying shoes, wiping one’s bottom in the lavatory.

p. 37

With digital technology, we drained reality dry.

p. 208

As much as there were parts that were very specific to the French society, there were just as many passages that universally applied. What it means to transition from being a girl, to a teenager, to a woman, the problems you face on the way, the reflections you might have and the transformations that you would go through as a person. All these found expression in “The Years” as well. The general idea of the book reminded me of Deborah Levy’s autobiography trilogy, consisting of three books: “Things I Don’t Want to Know“, “The Cost of Living” and “Real Estate“. Both women speak about what it means to be a writer, the discovery of one’s own identity in solitude, going through divorce and life after it, as well as having children and seeing them grow up.

Because in her refound solitude she discovers thoughts and feelings that married life had thrown into shadow, the idea has come to her to write ‘a kind of woman’s destiny’, set between 1940 and 1985. It would be […] a ‘total novel’ that would end with her dispossession of people and things: parents and husband, children who leave home, furniture that is sold.

p. 148

When she can’t sleep at night, she tries to remember the details of all the rooms where she has slept: the one she shared with her parents until the age of thirteen, the ones at the university residence and the Annecy apartment facing the cemetery.

p. 166

I was extremely glad to have discovered the book and the author for the first time thanks to the “Barcelona Women’s Book Club“. I felt like it would be an especially impactful read for women but even taken generally, it was an exceptional piece of writing. I would highly recommend it and I’m looking forward to reading further books by Annie Ernaux.

★★★★☆ (4/5)

Edition of English translation: ISBN 978-1-80427-052-3

Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2022 (first published in French in 2008)

Edition of French original: ISBN 978-2-040247-2

Éditions Gallimard, 2008