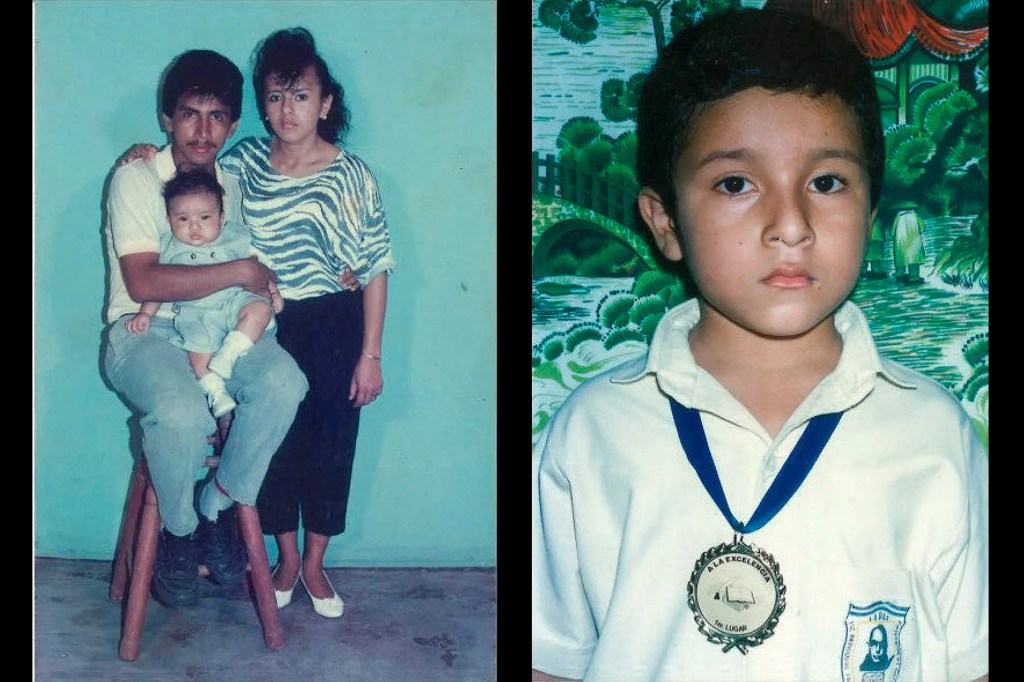

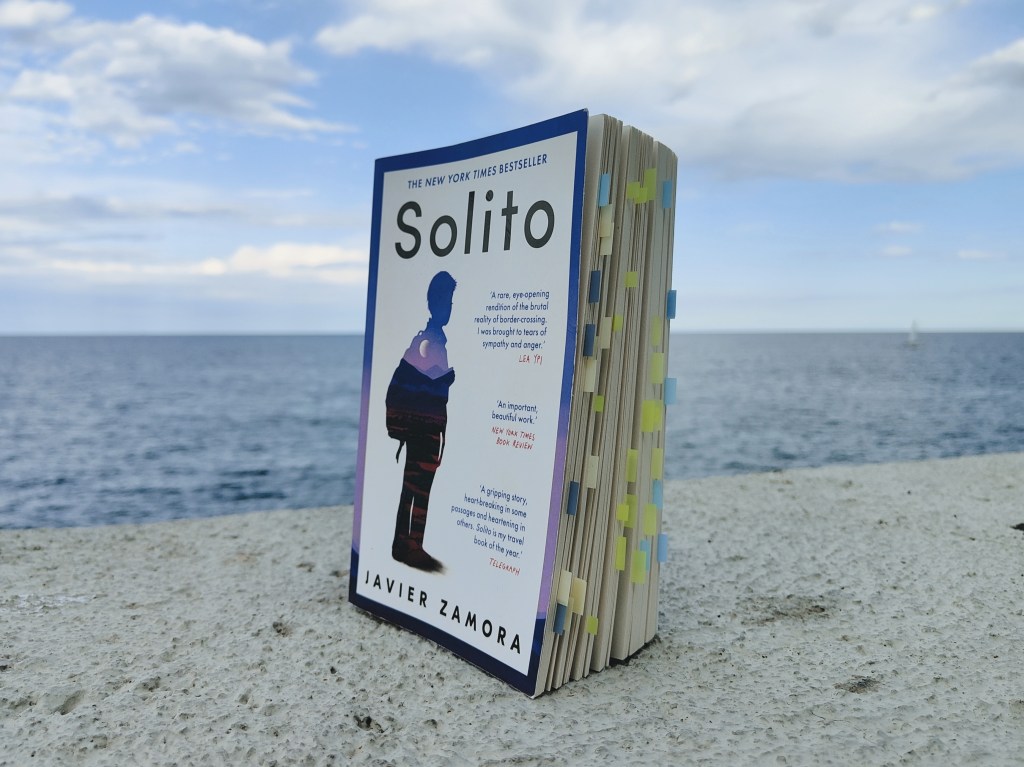

With “Solito” I was lucky to have come across a wonderful example of a memoir with a really impactful personal story. A 9 year old making his journey from El Salvador to the US in order to reunite with his parents was a narrative that instantly made me curious to find out more. All in all, it was a really impactful read, which made you forget that you were reading non-fiction at times. If you’re looking for an authentic insight into the world of someone who has put such an adventure behind him, this one might be the right next read for you. A novel that it made me think of was “American Dirt“, which dealt with a similar topic of migration from Mexico to the United States and which was extremely hyped around its publication in 2020. To all those who didn’t enjoy “American Dirt” (which was my case), I’d highly suggest giving “Solito” a try as an honest and heartfelt alternative. The way that the people the little boy encountered back then during his trip were so vividly described that it made them feel tangible and alive on the pages. This really permitted to establish a deep connection to them as a reader and I definitely felt moved by the time I reached the end. Javier Zamora, on the contrary to Jeanine Cummins, the author of “American Dirt”, managed to take the reader on an emotional rollercoaster while revealing his first hand experience of crossing three different countries before arriving in the US. He mentioned during a book reading that an important goal of writing his memoir was honoring the people that he came across on this journey.

The author’s first publication was “Unaccompanied“, a collection of poetry that was released in 2017. With this background, I was expecting a tale told in a creative and poetic kind of way. Similar to Ocean Vuong’s “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous“, which up until today is one of my all time favorite books stylistically. Nevertheless, the style ended up being quite simple, as the story was told from the perspective of Javier, the author back when he was 9 years old. Short sentences and childlike remarks were what really added their charm to the story. It was refreshing to see how the most difficult hardships can look like through the eyes of someone who is free from enormous existential worries and blind to the invisible dangers adults constantly have in mind. It brought oneself back to memories of the days when one’s biggest problem was not being liked by the boy or the girl one was interested in and being afraid of being judged for one’s body. As simple as the narrative was, there were still some beautiful phrases sprinkled throughout with unexpected comparisons or unusual descriptions. During a podcast, the author mentioned how he tried to write from the perspective of his current day self, as a 29 year old when he started his work on “Solito” because he still had feelings of shame connected to his childhood, without success. It was only through sessions with his therapist, meditation, reiki healing sessions and yoga that he was able to tap into the voice that felt authentic to him. This was the reason why he settled on telling the story through the eyes of him as a 9 year old.

I always talk to him second, after I talk to Mom. I remember everything about her. Her harsh voice like a wave crashing when she got mad at me. Her breath like freshly cut cucumbers.

p. 6

From time to time, as in the quote below, he slipped out from the point of view of a child, as he probably wouldn’t have been able to tell what having dyed black hair meant 😀

On his left hand, a gold watch. On top of his chest hair, three gold chains,thin, but each one thicker than the last. Black leather boots match his black leather belt. This outfit lets people know he’s not from La Herradura, not even from El Salvador. He looks more like the rancheros in Mexican novelas,except he doesn’t wear a sombrero; a baseball cap covers his bald spot, and dyed black hair protrudes from the sides.

p. 13

A comparison that really stood out to me was how the beauty of certain things is really subject to perspective and context. Whereas in the beginning he was marveling at the nature around him, with time, negative memories got associated with the same phenomenons, completely changing their meaning to him.

The sun peeks above the hills, but it’s almost gone below the horizon, painting everything bright red, deep orange, pink, lavender. It’s like all of the dust behind our truck flew to the sky. With the sunset, the dirt road turns a bright orange for a few minutes. Then there’s an opening. A clearing without any bushes. The ground redder and redder, brilliant, almost like blood.

Just one more day. One more walk. We leave tomorrow at dusk, Ramón said. Always at dusk in the desert. Sunrises, sunsets, I’m starting to hate them both.

p. 348

Two things that I wondered about was why the Spanish style of punctuation was used, meaning that inverted question marks and exclamation marks could be found throughout the entire text. The second was why so many words in Spanish were spread all throughout the book. You would find them randomly having been thrown into various phrases. To me, both things felt unnecessary at first. The punctuation felt as if it was an attempt of wanting to come off as more exotic to those who aren’t familiar with the Spanish language. Because why should they otherwise be used in English? I ended up looking up quite a few of the words in Spanish and even though they often were not decisive for understanding the plot, I would still see it as something that could be blocking a fluid reading flow (especially to those readers who don’t understand Spanish well). Fortunately I found a response for why this was intentionally done. Javier explained in a podcast how he was forced to lose his Salvadoran dialect to better assimilate, blend in with the English speakers but also to adapt to the way the Spanish Mexican majority spoke in the region where he grew up. The words in Spanish slang placed throughout the text specifically brought back the various dialects and ways of speaking of the different countries in South America.

Every night, between praying and sleeping, I lie in bed and think about them. ¿What type of bed do they sleep on? ¿Is it big? ¿Is it a waterbed like in the movies? ¿Are the sheets soft? I imagine cuddling right in the middle.

p. 4

The Baker is still here. His wife and all six of his kids también.

p. 5

‘Mucho nadar se va a ahogar usted,’ Carla says.

p. 169

We laugh even though it’s Carla’s go-to joke.

As a warning to potential readers, the start in the book was a very slow one. This brought me to the idea that it would be convenient to have some guides going along with books, giving suggestions on how to proceed with the reading, how many pages ideally to read in a single sitting and when to take breaks 😀 For “Solito”, I felt like you had to power your way through 70 out of 381 pages in one go in order to finally get to a point where your interest would be peaked by the events happening. If it wasn’t for a book club discussion deadline I was motivated by, it would have probably taken me much longer to get through it. Once you have made it over that obstacle though, you’d be in for a captivating read. In the end it also made sense why the first part had to be written in such a way, in order to find a balance with how the rest of the story unfolded. Showing the strong contrast between Javier’s former relaxed and calm days in his hometown La Herradura in comparison to the risky ordeal of a trip he then found himself on.

Upon finishing reading the story, my interest was sparked to find out more. To understand what the rates actually were that were charged by coyotes for helping migrants cross the border or what the author had to go through in order to be able to obtain legal documents in the US after his migration. It also awakened further reflections on the morality of certain decisions made my the people involved in Javier’s life. It was definitely a story that continued beyond its pages. A small insight is given in the very end when the author revealed what it took him to be able to put his story into writing. I dived straight into research mode upon finishing the book, reading and watching interviews with the author, as well as listening to podcasts in order to get responses. I’ll list the ones that I went through in the end of the review, if you have become curious as well. I was able to find out how Javier’s parents reacted to his book (his mom not having been able to make it past the first chapter and his father crying and apologising to him again, as he mentioned in this podcast), what the next project is that he will be working on or how risky it was for him to go back to El Salvador for the first time (involving having to self-deport himself, going through an interview round, risking being confined in his native country for 10 years, if everything went wrong, as he said in this podcast interview).

My parents and I have only spoken a few times about what happened to me those seven weeks. The first occurred immediately after Brown Mustache closed the apartment door, on our walk to the gas station, where the same taxi was waiting to take us to Phoenix International. […] The second happened years and years later, when I began writing poetry and started to process all of my emotions about—and the repercussions of—mymigration. When I confronted them, they both cried as they remembered what I smelled like when they first saw me—”piss, shit, sweat, a nasty stench” they’ve never forgotten. The other times we talked about those seven weeks were random questions via text or a quick phone call during the writing of this book.

p. 380

Mamá Pati y Papá Javi, I can’t imagine what reading this book must belike for you, what those weeks must’ve felt like. I hope you carry no guilt because I’ve long forgiven you. I love you, every single day.

p. 383

Wendy Carolina Franco, PhD, our weekly therapy sessions helped me tap into the well where I kept this story hidden. Gracias for helping me bring it into the light and for being the most perfect guide/bruja for my healing.

p. 383

One of the most impactful things within “Solito” for me was the example of the different types of people that we might meet on our path in life. Be it the good or the bad ones, their totality helping to put things in perspective. The way that people’s true spirit was revealed in the most extreme situations was simply masterfully described here. It’s a book that I would suggest to those who are interested in authentic personal stories but also as a positive example of writing from a child’s perspective done right. Even though the book wasn’t “perfect”, as I pointed out in some parts above, the most important thing about it for me was how much heart it had within it. Upon taking the time to try and get to know the author a bit better, I feel confident settling on a full 5/5 ★ rating. I admire his perseverance of wanting to tell such a personally difficult tale and it inspired me with the thought that each of us has something special to share with the world.

★★★★★ (5/5)

Edition: ISBN 978-0-86154-472-1

OneWorld Publications, 2022

Sources:

Graell, V. (2024): Javier Zamora: “Si no me hubiese ido del Salvador ahora estaría muerto, en la cárcel o sería evangélico. El Mundo. https://www.elmundo.es/cultura/literatura/2024/01/31/65b8ec59fdddff3a3c8b4586.html. Last accessed online: 10/05/2024.

KQED’s Forum (2022): “At age 9, Poet Javier Zamora Migrated from El Salvador Alone. In ‘Solito’ he tells that story”. https://open.spotify.com/episode/4QA32ubRKjiVMUKjyNODaB?si=CzyHxa-6Q36dnsPYN216xw. Last accessed on Spotify: 09/05/2024.

Penguin Random House (2023): Javier Zamora Shares His 3000 Mile Journey in His Memoir SOLITO | Inside the Book. https://youtu.be/zlQpqmVIwbc?si=WZrB6Eq9mcHug0NZ. Last accessed online: 10/05/2024.

Politics and Prose (2022): Javier Zamora — Solito – with Ana Patricia Rodríguez. https://www.youtube.com/live/U5UFmCQHb_I?si=xe9Y3thOScwbNhj0. Last accessed online: 09/05/2024.

Poured Over: The Barnes & Noble Podcast (2022): “Javier Zamora on SOLITO”. https://open.spotify.com/episode/4xGjDpFthp5FFSBBAMSJI5?si=-EiiDd–QyaihlMdWnx0nQ. Last accessed on Spotify: 09/05/2024.

Russell, P. B. (2022): Javier Zamora Carried a Heavy Load. He Laid It to Rest on the Page. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/05/books/javier-zamora-solito-migration.html. Last accessed online: 10/05/2024.